Prediction 7: Campaign Events and Preliminary Ensembling

Campaign Ground Game

October 21, 2024 – We are now just a day over two weeks from Election Day 2024. At this point in the election cycle, the air waves aren’t the only space jam-packed with campaign messaging. If you live in some of the most contested “swing” states, such as Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, Michigan, Arizona, Georgia, Nevada, or North Carolina, you may have had some campaign volunteers or canvassers knock on your door. Perhaps Trump or Harris, or their respective running mates, have stopped in your town for a rally, speech, or visit to a local business. All of these activities, the in-person interactions with a candidate or their representative, constitute a campaign’s ground game.

The activities of ground game, such as canvassing, visits, rallies, or speeches are opportunities for candidates to engage directly with voters. Candidates and campaigns strategize their ground game to generate enthusiasm with their core supporters, increase the turnout likelihood of their known supporters or those likely to support them, and even attempt to persuade swing voters.

Research generally agrees with the notion that targeted ground game activity produces a mild effect on election outcomes. But, in a close election, these small differences can add up. Therefore, it is a useful exercise to use ground game data to make some predictions for 2024.

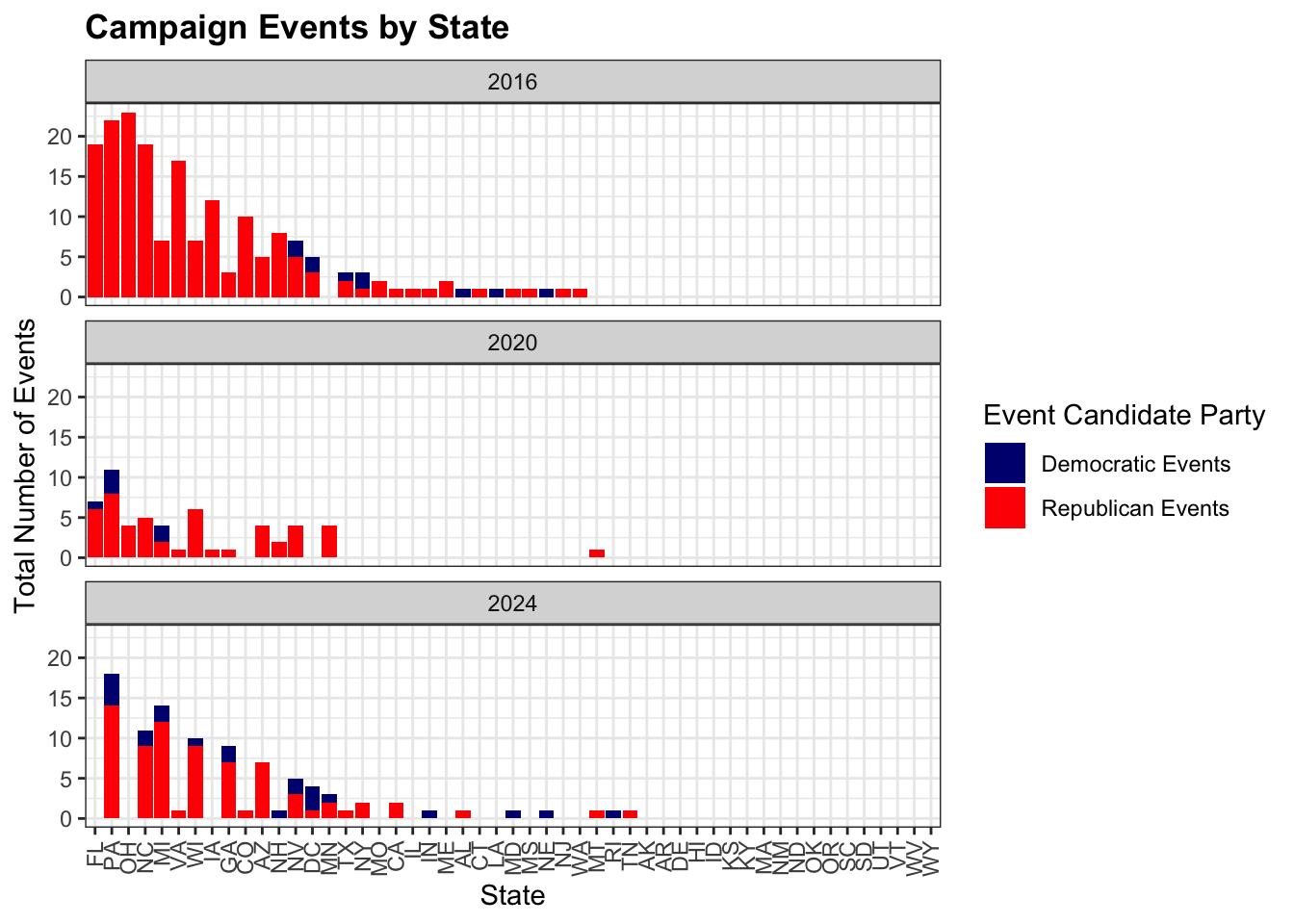

Unfortunately, ground game data is hard to come by. While there is data about the campaign office locations for previous elections, we do not have any for 2024. Therefore, to measure ground game, I’m using a logue of campaign events for each of the two presidential candidates from the 2016, 2020, and 2024 elections. These include rallies, speeches, town halls, or campaign visits made by the major presidential candidates: Trump, Clinton, Biden, Harris; and/or their respective running mates, from after their convention up to about 3 weeks before the election. Judging by the plot below, it is clear that candidates concentrate their events in key swing states, while never holding events in almost half of all states. It is also clear that Trump is an incessant rally holder, as he has held the overwhelming majority of campaign events compared to each Democrat he has faced. This makes our data available for prediction purposes extremely sparse, as we have not observed campaign events of any kind in a large number of states, let alone a sufficient number of Democratic candidate events.

Nonetheless, I fit an OLS regression model using data from the 2016 and 2020 elections for each state. My predictor variables of interest included the number of events attended in a given state either by the Democratic presidential candidate, Republican presidential candidate, or either of the vice presidential candidates, as well as lagged vote share from the previous election. To reduce prediction error, I used elastic-net regularization to check for the strongest predictors. This resulted in me dropping the variable for the number of events attended by the Democratic presidential candidate. The remaining event variables all had extremely small effects compared to the lagged vote share, but I included them for the sake of the exercise. My ground game event model predicting Democrat two-party vote share yielded an adjusted r-squared of 0.9297, due to the inclusion of lagged vote share. Otherwise, the data would be too sparse for any sort of prediction. Using 2024 campaign event data, I predicted Harris’ two-party vote share in each state. The prediction results are shown below.

This simple ground game campaign event model predicted that Republican former president Donald Trump will win the 2024 election with 306 electoral votes, compared to Democrat Vice President Kamala Harris’ 232 electoral votes. In this scenario, Trump narrowly flips back the five states (Wisconsin, Michigan, Pennsylvania, Arizona, and Georgia) by less than 1 percentage point. This suggests that if Harris and Walz want to tilt the scales of the election in her favor, she should ramp up her event schedule to compete with Trump’s prolific amount of rallies.

Prediction by Ensembling

One flaw of using the number of campaign events to predict vote share is that the data does not account for the size of the events. One could hypothesize that having a small number of extremely large rallies has a different effect than many small stumping events. Additionally, what is the exact effect of these campaign events anyway? Do in-person events like rallies and speeches sway voters, considering that the people who most likely attend these events are ardent supporters? Considering campaign events are one small facet of a candidate’s path to victory, can they even make a good prediction?

These questions are why we may not want to put all of our prediction eggs in one model basket. Ensembling, or putting the predictions of models together, allows us to make more informed and accurate predictions, as we are able to account for more predictors.

To create a more accurate prediction of the election based on campaign-related factors, I ensembled my ground game model predictions with three other models. The first two models are simple models based on polling data. One of the drawbacks of the spare campaign event data was that I had to construct a singular pooled model to predict all states. For the poll models, I constructed unpooled OLS regressions for each state based on FiveThirtyEight’s state polling averages 3 weeks before the election. In fitting these models, I added exponential weights by election year, for data from the 1976 to 2020 elections, to account for the fact that more recent elections will be more informative for 2024 predictions. The first polling average model includes a simple difference in polling average between the Democratic and Republican candidates to predict Democratic two-party vote share, while the second model includes these same variables plus year as a numeric variable to account for time trends. The first model resulted in a mean adjusted r-squared of 0.33 across states, while the second model had an adjusted r-squared of 0.52 across states.

The third additional model might be familiar, it is my pooled FEC contributions model from last week (see my “Money is Power: Campaign Finance” article for more information on how I created this OLS model). In short, this model has an adjusted r-squared of 0.93 and an out-of-sample k-fold cross validation RMSE of 5.77.

For the ensemble model, I estimated a prediction for each state by calculating the weighted average of the predictions from the four models. Because of polling’s historically good predictive power, I allotted 50% weight for both polling models. I divided this weight between each model based on the average RMSE across the two unpooled models. The simple polling average model had an average RMSE of 4.52, while the polling average and year model had an average RMSE of 5.43, which translated into a ~0.273 and ~ 0.227 weight respectively. As for the other 50% weight, the FEC contributions model received 0.3, and the ground game model received 0.2 weight, because the FEC contributions model simply is built on more data and is more suitable for accurate prediction. Additionally, the polling averages models could not make predictions for a majority of states, because statewide polling has not been conducted in every state in the 2024 election cycle yet. Therefore, for states without polling model predictions, their weighted average uses predictions from only the ground game and FEC contribution models. The results of this weighted average ensemble model is shown below.

This ensemble model predicts that Republican former president Donald Trump will win the 2024 election with 278 electoral votes, compared to Democrat Vice President Kamala Harris’ 260 electoral votes; an extremely close election. But, the prediction becomes even closer when you consider that the model predicts Harris will get 49.99456% of the two-party vote share! If my model is off by a fraction of a decimal point, then Harris could win the 2024 presidential election with exactly 270 electoral votes! It literally does not get any closer than this. In addition to Wisconsin, the model predicts that the six other swing states will also be extremely close calls, indicating that the election is still any candidate’s game.

While preliminary, this ensemble model demonstrates how in my final prediction, I will combine components of many of the predictive models I have made in the past seven weeks. Stay tuned as I try to make sense of this extremely contentious and uncertain election!